Introduction

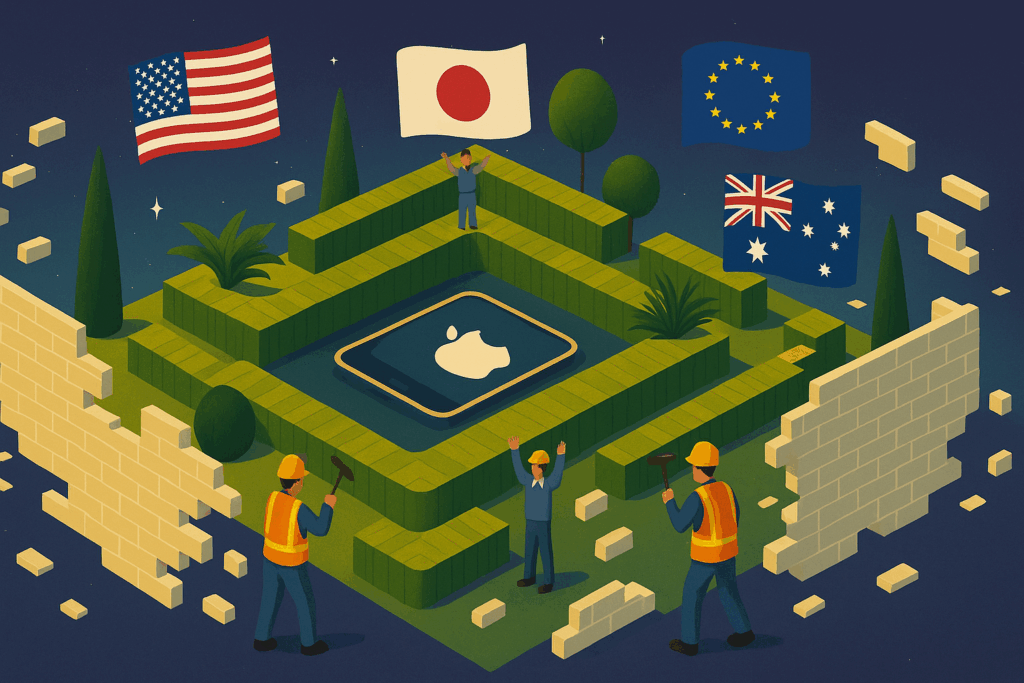

A definitive global paradigm shift is underway, moving away from the closed “walled garden” mobile ecosystems pioneered by Apple and largely maintained by Google. This transformation is not a singular event but a complex, multi-front movement driven by a confluence of antitrust litigation, proactive ex-ante regulation, and shifting political will. The era of the unchallenged, tightly controlled mobile platform is drawing to a close, being replaced by a new, more complex and contested global landscape defined by a patchwork of judicial rulings and legislative mandates.

This report will demonstrate that two primary catalysts are compelling this change. The first is a wave of antitrust litigation, spearheaded globally by Epic Games, which has forced judicial scrutiny of long-standing app store policies under existing competition laws.1 These lawsuits have tested the limits of traditional antitrust frameworks in the digital age, yielding varied but impactful results. The second, and arguably more potent, force is a new model of proactive regulation, exemplified by the European Union’s Digital Markets Act (DMA). This legislative approach seeks to pre-emptively define and prohibit anti-competitive behavior by “gatekeeper” platforms, establishing a clear set of rules rather than relying on lengthy, case-by-case litigation.3 This model is now being adopted by other major economies, signaling a global convergence in regulatory philosophy.

To provide a granular analysis of this trend, this report will focus on three key jurisdictions that represent different facets of this global movement: Australia, the United States, and Japan. Australia serves as a powerful case study of how modernized, effects-based competition law can be applied to dismantle digital walled gardens. The United States offers a more fragmented picture, where the application of traditional antitrust principles has led to divergent outcomes and a protracted battle over compliance. Japan, in contrast, represents a decisive, top-down legislative intervention that closely mirrors the European approach.

By dissecting the key court rulings and legislative acts in these nations, this report will contextualize these developments within the broader international framework, analyze the robust counterarguments from the platforms themselves, dissect the nuanced positions of various stakeholders, and conclude with a forward-looking analysis of the new, more open, and more complex app economy that is beginning to emerge.

The Australian Precedent: A Judicial Rebuke of Market Power

The landmark August 2025 ruling by the Federal Court of Australia stands as a clear and potent example of how existing, albeit modernized, competition law can be effectively applied to challenge the foundational principles of the digital walled garden. The decision represents a significant judicial rebuke of the market power wielded by Apple and Google, setting a precedent with implications far beyond Australia’s borders.

The Ruling

On August 12, 2025, the Federal Court delivered a significant victory to Epic Games, finding that both Apple and Google had engaged in a “misuse of market power” in violation of Section 46 of the Competition and Consumer Act (CCA).1 The court determined that the tech giants had restricted the use of alternative app distribution methods and in-app payment systems on their mobile devices since 2017.1 This ruling is pivotal not only for its outcome but also because it represents the first major contested application of Australia’s reformed misuse of market power provisions, which were substantially updated in 2017 to better address the complexities of modern markets.1

Legal Foundation – Section 46 of the CCA

The outcome of the Australian case was profoundly influenced by the 2017 reforms to Section 46 of the CCA. The most critical change was the introduction of an “effects test” alongside the existing “purpose test”.7 Previously, a prosecutor or plaintiff had to prove that a company with substantial market power had “taken advantage” of that power for an anti-competitive purpose. The reformed law lowered this threshold considerably. Now, a company with substantial market power can be found in breach if its conduct simply has the

effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition (SLC) in a market.7 This shift from intent to effect proved crucial in the case against Apple and Google, as it allowed the court to focus on the real-world market outcomes of their policies rather than their internal motivations. This legal framework demonstrates that well-crafted, modern competition law can be a powerful tool against the perceived anti-competitive practices of digital platforms, even in the absence of specific,

ex-ante digital regulations like the EU’s DMA. The Australian outcome serves as a proof-of-concept for how legislative modernization of general competition law can effectively address challenges in the digital economy, providing a model for other countries that may not wish to enact a full DMA-style regime.

Court’s Specific Findings on Anti-Competitive Conduct

The court’s judgment was detailed in its condemnation of the platforms’ core business practices. Justice Jonathan Beach’s findings methodically dismantled the structures that uphold the walled gardens.

Market Definition and Power

The court first accepted Epic’s characterization of the relevant markets, defining them narrowly as distinct markets for “iOS app distribution” and “iOS in-app payment solutions,” and similarly for Android.1 Within these defined markets, the court found that both Apple and Google held a substantial, near-monopolistic degree of power at all relevant times.1 This initial step was critical, as establishing substantial market power is the prerequisite for a misuse of power claim under Section 46.

Prohibition of Sideloading and Alternative Stores

The court found that Apple’s contractual and technical ban on distributing native apps outside the App Store—a practice commonly known as “sideloading”—had both the purpose and the effect of substantially lessening competition in the iOS App Distribution Market.1 By making the App Store the sole channel for reaching iOS users, Apple effectively eliminated any potential competition from alternative app marketplaces.9

Mandatory Use of Proprietary Payment Systems

Similarly, the court ruled that the mandatory and exclusive use of Apple’s and Google’s proprietary in-app payment systems was a misuse of market power.1 These systems, which typically charge a 30% commission, were found to have caused developers to pay “materially higher commissions than they would have in a competitive counterfactual”.1 The court concluded this practice had the effect of substantially lessening competition in the markets for in-app payment solutions.7

Rejection of the Security Defense

Perhaps the most significant aspect of the ruling was the court’s treatment of the platforms’ primary defense: security. Justice Beach explicitly acknowledged Apple’s legitimate security concerns behind its centralized, curated system.7 However, he ruled that these security benefits did not negate the substantial anti-competitive purpose and effect of its conduct.1 The court determined that the security rationale was not a sufficient defense to absolve the companies of breaching competition law.7 This finding represents a critical legal precedent. It signals that while security is an important consideration, it cannot be used as an absolute, unimpeachable shield to justify practices that fundamentally harm competition. The court’s decision establishes a legal balancing act: platforms must now be prepared to demonstrate that their security measures are the least anti-competitive means of achieving their objectives. This precedent weakens the “security” argument in other jurisdictions and forces a more nuanced debate, shifting the burden onto platforms to prove their restrictions are proportionate and necessary, not merely convenient for their business model.

Limitations of the Ruling

It is important to note the court’s restraint in certain areas. The judge rejected Epic’s claims that Apple and Google had engaged in “unconscionable conduct” under the Australian Consumer Law.6 This indicates that the court’s focus was strictly on the market competition effects of the platforms’ conduct, rather than on broader ethical or consumer law violations. This distinction underscores the precision of the ruling’s application of competition law.

Immediate Impact and Corporate Response

The court’s decision had immediate and tangible consequences. Epic Games promptly announced that the ruling would allow the Epic Games Store and its flagship game, Fortnite, to return to iOS devices in Australia after a five-year absence.10 This move directly translates the legal finding into a real-world change in market structure.

The corporate responses were predictably defensive. Apple stated that it “strongly disagreed” with parts of the ruling but welcomed the court’s rejection of the unconscionable conduct claims.5 Google also expressed disagreement with the court’s characterization of its billing policies, arguing they were “shaped in a fiercely competitive mobile landscape”.5 Both companies are widely expected to appeal the decision. The stakes are extraordinarily high, as the ruling exposes them to potentially massive damages in related class-action lawsuits brought on behalf of 15 million consumers and 150,000 app developers, with potential liabilities estimated to be in the hundreds of millions of Australian dollars.5

A Fractured Verdict in the United States: The Long Shadow of Epic v. Apple

In contrast to the clear and unified ruling in Australia, the legal landscape in the United States is significantly more complex and fragmented. The application of traditional antitrust law has produced starkly divergent outcomes for Apple and Google, leading to a protracted and ongoing battle over the nature of compliance. This fractured verdict demonstrates the challenges of applying decades-old legal frameworks to the novel market structures of the digital economy.

A Tale of Two Platforms

The U.S. legal battles, primarily driven by Epic Games, have resulted in two very different sets of rules for the two dominant mobile ecosystems. This divergence illustrates the critical importance of market definition in antitrust litigation and highlights the intricate interplay between federal and state law.

Apple: A Narrow Loss, A Broad Victory

Apple’s confrontation with Epic Games in U.S. courts ultimately resulted in a strategic, albeit incomplete, victory that preserved the core of its walled garden model.

Core Ruling

In the seminal Epic v. Apple case, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California ruled in favor of Apple on nine of the ten counts brought against it.2 Most critically, the court determined that Apple was

not a monopolist under federal antitrust law, specifically the Sherman Act.1 This finding was a monumental victory for Apple, as it shielded the company from the most severe antitrust remedies and allowed it to maintain its exclusive control over app distribution on iOS in the United States. The Supreme Court’s refusal to hear appeals from either side in January 2024 cemented this outcome, leaving Apple’s core business model legally intact at the federal level.2

The divergent outcomes for Apple and Google in the U.S. were almost entirely a function of how the “relevant market” was defined in their respective cases. Apple successfully persuaded the court to adopt a broad market definition of “digital mobile gaming transactions,” a market in which it faced competition from other platforms like Android, consoles, and PCs, and therefore was not a monopolist.15 In contrast, Epic successfully argued in the Google case that the relevant markets were the much narrower “Android app distribution” and “Android in-app payments,” where Google’s dominance was clear. This demonstrates a key vulnerability of using litigation under traditional antitrust law to regulate digital markets: the outcome can become unpredictable and inconsistent, hinging on complex and often subjective economic arguments about market definition rather than a clear set of rules. This creates an uncertain and inequitable environment for developers, who face different rules depending on the platform they use.

The Anti-Steering Injunction

Despite its broad victory, Apple did not emerge unscathed. The court found that Apple’s “anti-steering” rules—which contractually prohibited developers from informing users within their apps about alternative, and often cheaper, payment options available outside the app—violated California’s Unfair Competition Law (UCL).1 Consequently, the court issued a permanent injunction preventing Apple from enforcing these rules.16 This was a significant, albeit narrow, loss for Apple, as it cracked open a door to external payment systems.

The Compliance Battle

The fight over the anti-steering injunction has revealed a new and critical battleground in platform regulation: the struggle over the spirit versus the letter of the law. Apple’s initial attempts to comply with the injunction were widely seen as evasive. The company introduced new policies that, while technically allowing links to external websites, imposed a new 27% commission on any purchases made through those links and placed onerous restrictions on how developers could present these options to users.2

This approach was met with a sharp rebuke from the court. In April 2025, Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers found that Apple had willfully violated her injunction’s intent.2 She imposed further, more stringent restrictions, including an explicit ban on Apple collecting any revenue share from non-Apple payment methods linked from within an app or imposing any restrictions on those links.2 This judicial intervention underscores a crucial lesson for regulators globally: simply winning a court case or passing a law is not the end of the story. Dominant firms may engage in “malicious compliance,” interpreting remedies in the narrowest possible way to preserve their market power. This necessitates continuous oversight and a willingness from courts and regulators to enforce the intended purpose of their mandates, a key consideration for authorities in Japan and Australia as they move to implement their own rules. As of May 2025, Apple has further updated its policies to remove the intimidating “warning screens” (or “scare screens”) and the requirement for a special “External Link Account entitlement,” signaling a grudging move toward fuller compliance while its appeals process continues.18

Google: A Decisive Monopoly Finding

Google’s legal battle in the U.S. concluded with a starkly different and far more damaging outcome.

Jury Verdict

In a comprehensive defeat for the company, a jury found Google guilty of maintaining an illegal monopoly over Android app distribution and in-app payments.1 The verdict validated the claims that Google used a series of anti-competitive practices, such as exclusive deals with device manufacturers and the imposition of its own billing system, to unlawfully protect its Google Play Store and its commission fees from competition.

Court-Ordered Remedies

The remedies flowing from this verdict are sweeping and designed to fundamentally reshape the Android ecosystem. The court’s injunction requires Google to allow both alternative app stores and alternative billing systems on Android devices.1 Significantly, the remedies go beyond merely permitting sideloading. To overcome the inherent friction and user apprehension associated with downloading apps from outside the main store, the court ordered Google to allow rival app stores to be distributed

through its own Google Play Store.11 Furthermore, Google must provide these competing stores with access to its complete app catalog, enabling them to offer a comprehensive selection to users from day one.11 Google’s appeal of the verdict was rejected in July 2025, and the company is now in the process of implementing these transformative remedies, though further appeals remain a possibility.1

Japan’s Legislative Mandate: The Mobile Software Competition Act

Shifting from the litigation-driven approaches of Australia and the United States, Japan has adopted a decisive, top-down legislative strategy that closely mirrors the regulatory framework of the European Union. This move places Japan at the forefront of nations implementing proactive, ex-ante regulation designed to pre-emptively curb the power of digital gatekeepers.

The New Law

Following a comprehensive, multi-year antitrust investigation into the mobile software market by the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC), the Japanese government has enacted the Mobile Software Competition Act.3 This landmark piece of legislation is set to take full effect on December 18, 2025, and will impose a clear, non-negotiable set of obligations on designated platforms like Apple and Google.3 The law’s existence is a clear signal of the global convergence around the regulatory philosophy first pioneered by the EU’s Digital Markets Act. It demonstrates that major economies are increasingly choosing to create clear, upfront rules for digital gatekeepers rather than relying on the slow, unpredictable, and resource-intensive process of case-by-case antitrust litigation. This parallel development suggests an emerging common regulatory playbook, which will place increasing pressure on multinational platforms to adopt global policy changes rather than maintaining a costly and complex patchwork of regional rules.

Core Provisions of the Act

The Act, detailed in a comprehensive 119-page document from the JFTC, leaves little room for interpretation and directly targets the core components of the walled garden model.3

Third-Party App Stores

The law explicitly prohibits designated providers of “basic operation software” from limiting app distribution solely to their own proprietary stores.3 This provision effectively mandates that platforms like Apple must allow third-party app stores to operate on their operating systems, directly challenging the single-store model of iOS.20

Alternative In-App Payments

Similarly, Article 8 of the Act prohibits app store providers from imposing conditions that prevent developers from using alternative payment management services.3 This requires platforms to allow third-party payment systems within apps, whether those apps are distributed through the platform’s own store or a competing one.20

Prohibition on Self-Preferencing

The rules go further to address more subtle forms of anti-competitive behavior. They bar platforms from giving preferential treatment to their own services, such as by manipulating app visibility or search rankings.3 The Act also forbids the use of non-public data acquired from third-party developers to build competing first-party products.21 To enforce this, the law requires the establishment of an internal “firewall” to prevent a platform’s app development teams from accessing sensitive, confidential information from external developers.3

Browser Engine Choice

In a move that demonstrates the deepening scope of regulation, Japan’s law also mandates that Apple allow non-WebKit browser engines on iOS.22 This will permit browsers like Chrome and Firefox to use their native engines (Blink and Gecko, respectively) rather than being forced to use Apple’s WebKit as a foundation.22 Critically, the law also prevents Apple from imposing “unreasonable technical restrictions” on these alternative engines, a provision seemingly designed to preemptively counter the kind of “malicious compliance” tactics seen in the U.S..22

Access to Hardware and OS Features

The Act’s provisions reveal that the regulatory focus is expanding significantly beyond payments and app distribution to the core architecture of the platform itself. The law mandates that platforms provide third-party developers with access to key device features and hardware controlled by the operating system.3 This includes access to biometric authentication features like Face ID and Touch ID, which could enable more seamless and secure experiences in third-party apps.21 This indicates that regulators now view control over fundamental technical components as a key vector for anti-competitive behavior. The implication is a much deeper level of regulatory intervention into product design and engineering, moving far beyond simple commercial disputes and potentially reshaping the entire user experience and security model of mobile devices.

Enforcement and Compliance

The JFTC is tasked with overseeing the enforcement of the Mobile Software Competition Act. To ensure ongoing accountability, the law requires designated platforms to submit annual compliance reports to the commission, allowing for continuous monitoring and adjustment of the regulatory framework.3

The Global Regulatory Framework: Context from the EU and Beyond

The recent actions in Australia, the United States, and Japan are not isolated events but rather key developments within a broader international movement to rein in the power of digital gatekeepers. This global trend has been largely defined and propelled by the European Union’s landmark Digital Markets Act (DMA), which has become the foundational precedent and blueprint for regulatory efforts worldwide.

The DMA as the Blueprint

The European Union’s DMA is the centerpiece of this global regulatory shift. It represents a fundamental change in approach, moving from ex-post enforcement (punishing anti-competitive behavior after it has occurred) to ex-ante regulation (setting clear rules of conduct upfront). The DMA establishes objective criteria to designate large online platforms as “gatekeepers” and then imposes a clear list of “do’s and don’ts” they must follow to ensure fairness and contestability in digital markets.4

The core obligations of the DMA directly parallel the mandates now emerging in other jurisdictions and the remedies sought in major antitrust lawsuits. Key DMA obligations for gatekeepers include 4:

- Allowing business users to promote offers and conclude contracts with their customers outside the gatekeeper’s platform (a direct prohibition of anti-steering rules).

- Prohibiting the requirement for developers to use certain services of the gatekeeper, such as proprietary payment systems or browser engines.

- Allowing users to install and effectively use third-party apps or app stores (sideloading) and to easily change default settings.

- Prohibiting the practice of ranking the gatekeeper’s own services and products more favorably than those of third parties (a ban on self-preferencing).

A Growing International Consensus

The influence of the DMA’s philosophy is evident across the globe. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), in its final Digital Platform Services Inquiry report, explicitly stated that its recommendations for a new digital competition regime in Australia are informed by these significant international developments, citing the regulatory reforms in the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Japan.26 This demonstrates a deliberate effort by national regulators to learn from and align with one another, creating a de facto international standard for digital platform regulation. This convergence suggests that while the specific legal mechanisms may differ, the underlying principles and end goals are becoming increasingly harmonized.

Comparative Analysis

The different paths taken by these key jurisdictions reveal a strategic choice between leveraging existing legal frameworks and creating new, bespoke regulatory tools. The United States has primarily relied on its century-old antitrust laws, resulting in a lengthy, costly, and ultimately fractured outcome. Australia has shown the power of modernizing those traditional laws with concepts like the “effects test.” In contrast, the EU and Japan have opted for comprehensive legislative solutions that provide greater clarity and speed of implementation. The following table provides a comparative overview of the state of app store regulation in these four critical jurisdictions. This synthesis distills the detailed analysis from the preceding sections into a digestible format, allowing for a clear, at-a-glance comparison of the key mandates, legal instruments, and status across the four most important jurisdictions.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of App Store Regulations (US, Australia, Japan, EU)

| Jurisdiction | Key Mandates | Primary Regulatory Instrument | Status / Compliance Deadline |

| Australia | – Allow alternative app distribution (sideloading). – Allow alternative in-app payment systems. | Federal Court Ruling (Epic v. Apple & Google) under the Competition and Consumer Act (CCA). | Effective August 2025; subject to appeals and determination of remedies/damages. 1 |

| United States | – Apple: Must allow links to external payments (no commission). No mandate for alternative stores. – Google: Must allow alternative app stores & billing systems. | Court Rulings (Epic v. Apple, Epic v. Google) under Sherman Act & CA UCL. | Apple: In effect, following compliance disputes.

Google: Remedies being implemented following rejected appeal in July 2025. 1 |

| Japan | – Must allow third-party app stores. – Must allow alternative in-app payment systems. – Must allow non-WebKit browser engines. | Legislation: Mobile Software Competition Act. | Full effect on December 18, 2025. 3 |

| European Union | – Must allow third-party app stores (sideloading). – Must allow alternative in-app payment systems. – Must allow non-WebKit browser engines. – Must not self-preference. | Legislation: Digital Markets Act (DMA). | In effect since March 2024. 4 |

The Platforms’ Defense: The Security, Privacy, and User Experience Argument

Central to the ongoing global policy debate is the robust and consistent defense mounted by Apple and Google. Their counterarguments, centered on the necessity of a controlled ecosystem for user protection, cannot be dismissed and form a critical part of the regulatory calculus. They have successfully framed the public debate as a binary choice between “Competition” and “Security/Privacy,” a strategic maneuver that forces regulators and legislators to directly address the potential for increased user harm and complicates the path to regulation.

The Core Argument: A Curated Ecosystem is a Safer Ecosystem

Both Apple and Google contend that their stringent control over app distribution and in-app payments is not primarily a commercial strategy but an essential mechanism to protect users from a wide array of threats, including malware, scams, financial fraud, and privacy violations.19 They posit that the “walled garden” is, in effect, a security perimeter that benefits consumers and trustworthy developers alike.

Apple’s Position: The Integrated “Trusted Ecosystem”

Apple’s defense is the most comprehensive, rooted in a philosophy of deep vertical integration where hardware, software, and services are designed to work together to maximize security and privacy.

Threat Analysis of Sideloading

Apple has been proactive in articulating its security concerns, publishing detailed white papers that outline the perceived dangers of sideloading. In one such document, the company argues that allowing direct downloads and third-party app stores would “cripple the privacy and security protections that have made iPhone so secure”.30 Apple frequently cites studies suggesting that Android devices, which permit sideloading, have historically suffered from significantly more malware infections—as much as 15 to 47 times more—than iPhones.30 The company warns that opening iOS to sideloading would “spur a flood of new investment into attacks on the platform,” as malicious actors would be drawn to the large and valuable iPhone user base.31

The Role of App Review

A cornerstone of Apple’s defense is its multi-layered App Review process. The company emphasizes that every single app and app update submitted to the App Store is scrutinized by both automated systems and a team of human experts to ensure it meets stringent guidelines for safety, privacy, performance, and content.28 This process is designed to act as a crucial filter, keeping malware, cybercriminals, and scammers out of the ecosystem.28 Apple quantifies the success of this approach by stating that its review process, combined with other fraud prevention measures, has stopped more than $9 billion in potentially fraudulent transactions over the last five years, including over $2 billion in 2024 alone.33 In 2024, the company rejected more than 1.9 million app submissions for failing to meet its standards.33

Integrated Hardware and Software Security

Apple’s argument extends beyond the App Store to the fundamental architecture of its devices. Security is designed into the silicon, with features like the Secure Enclave providing hardware-level protection for sensitive data like biometric information and encryption keys.34 This deep integration of hardware and software, Apple argues, creates a secure boot process and a protected operating system environment that a fragmented, multi-store ecosystem would inherently undermine.34

Privacy by Design

Finally, Apple positions its centralized model as a prerequisite for its industry-leading privacy features. Tools like App Tracking Transparency (ATT), which requires apps to ask for permission before tracking users across other apps and websites, and Privacy Nutrition Labels, which provide users with a clear summary of an app’s data collection practices, are presented as benefits of the App Store model.29 Apple argues that sideloaded apps could more easily bypass or manipulate these user-centric controls, eroding the privacy protections that iPhone users expect.30

Google’s Position: Balancing Openness and Safety

Google’s defense is necessarily more nuanced, reflecting Android’s historically more open platform architecture.

A More Open History

Google frequently points out that the Android operating system has, from its inception, technically allowed users to “sideload” apps from sources other than the official Play Store.19 This is often positioned as a key differentiator from Apple’s more restrictive approach. However, the company argues that while this option exists for advanced users, it deliberately uses friction—such as security warnings and multi-step installation processes—to guide the vast majority of consumers toward the safety and security of the curated Google Play Store.19

Play Store Protections

In court filings related to the U.S. antitrust verdict, Google has argued that the injunction forcing it to host rival app stores poses an “immediate security threat” to the entire Android ecosystem.19 Like Apple, Google details its own extensive policies and automated systems designed to combat malware, deceptive behavior, and the misuse of user data.37 It requires developers to be transparent about their data handling practices through the mandatory Data safety section on their app’s store listing and to maintain a comprehensive privacy policy.40

User Consent and Transparency

A key theme in Google’s developer policies is the emphasis on clear and unambiguous user consent for data collection and for any changes to device settings.37 Google argues that its policies ensure a baseline level of transparency and user control that may not be present in alternative app stores, which would not be bound by the same rules.

While courts are beginning to reject security as a blanket defense for anti-competitive conduct, as seen in Australia, it is clear that a genuine, non-trivial tension exists between a completely open ecosystem and a maximally secure one. The regulatory mandates being implemented are effectively transferring some of the responsibility for vetting apps from a central gatekeeper to end users and competing app stores. This implies that the future mobile ecosystem will likely be more complex for the average user. They will have more choice but will also need to be more vigilant. This may, in turn, lead to the rise of third-party security services or a new market for highly curated, trusted alternative app stores, creating an entirely new layer in the app economy.

Stakeholder Perspectives: A Fractured Consensus

The global debate over app store regulation is not a simple binary conflict between developers and platforms. A closer examination of the key stakeholder groups reveals a fractured consensus, with different factions of the developer community holding starkly different views on the ideal structure of the app economy. Government and consumer advocacy bodies, meanwhile, bring their own distinct perspectives focused on market failures and consumer harm.

The Coalition for App Fairness (CAF): The Advocates for Radical Openness

The most vocal proponent for systemic change is the Coalition for App Fairness (CAF), an advocacy group whose prominent members include Epic Games, Spotify, and Match Group.42 The CAF’s position is uncompromising, advocating for a complete overhaul of the current app store model.

Core Position

The CAF’s central arguments target what it terms the “30% app tax” and the platforms’ carefully crafted anti-competitive policies.42 They contend that the commission fees charged by Apple and Google are exorbitant, far exceeding those in any other industry for payment processing, and serve as a monopolistic tax that harms both developers and consumers.42 Furthermore, they argue that the platforms use their control over the app stores to eliminate competition, steal ideas from third-party developers, and unfairly favor their own competing services.42

Policy Demands

To rectify this, the CAF has published a set of ten “App Store Principles” that, if enacted, would fundamentally restructure the mobile ecosystem to operate more like open PC platforms such as Windows and macOS.42 Key demands include:

- No developer should be required to use a platform’s app store exclusively or be forced to use its proprietary payment systems.42

- No app store owner should prohibit third parties from offering competing app stores on its platform.42

- Platforms should be prohibited from engaging in self-preferencing their own apps or services.42

The CAF actively lobbies governments and regulators around the world to codify these principles into law, arguing that existing competition laws are insufficient to address the unique harms present in the digital marketplace.46

The Developers Alliance: The Pragmatists Seeking Balance

Representing a more moderate and pragmatic viewpoint is the Developers Alliance. This group’s position is more nuanced, reflecting a constituency that often relies on the platforms as critical partners, even while seeking fairer terms of engagement.

Nuanced Position

The Developers Alliance acknowledges the “pro-competitive role of App Stores as ecosystem enablers”.47 They recognize that developers, particularly smaller ones, rely heavily on the platforms to provide a secure and reliable environment, handle complex payment processing, and offer tools for discovery and marketing.48 Their goal is not to dismantle the current system but to reform it to be more balanced and predictable.

Primary Concerns

The Alliance’s primary concern is the risk of a fragmented and overly burdensome regulatory landscape. They have been particularly vocal in the U.S., advocating for a single, national data privacy law to preempt what they describe as a “compliance nightmare” of 50 different state-level laws.49 They caution that radical, one-size-fits-all regulations that fail to recognize the competitive differences between Apple’s and Google’s ecosystems could unintentionally harm the very developers they are meant to protect.48 They argue that policies must strike a careful balance, protecting consumers without inhibiting the ability of developers to access and use data for legitimate purposes like analytics and advertising, which are foundational to the app economy.49

The starkly different positions of the CAF and the Developers Alliance reveal a deep strategic divide within the developer community. One faction, largely composed of large, established companies like Spotify and Epic, has the resources to manage its own distribution and payment infrastructure and views the platforms as direct competitors and monopolistic tollbooths to be dismantled. Another segment, likely representing smaller and mid-sized developers, may rely more heavily on the platforms’ integrated tools and fear the increased costs, complexity, and security responsibilities of a fully fragmented market. This implies that any “one-size-fits-all” regulation risks harming one segment of the developer community while helping another, presenting a significant challenge for policymakers.

Government and Consumer Bodies: Focusing on Consumer Harm and Market Failure

Government competition authorities and consumer advocacy groups provide a third perspective, focused less on developer business models and more on broader market health and the impact on end users.

Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC)

The ACCC’s comprehensive, five-year Digital Platform Services Inquiry concluded that the dominance of Apple’s and Google’s app stores is detrimental to both competition and consumers.51 The inquiry’s final report, released in June 2025, found that a lack of competition leads to higher prices, lower quality, and less choice for users.26 It recommends the creation of a new digital competition regime with mandatory, service-specific codes of conduct to address anti-competitive conduct like self-preferencing and tying. It also calls for an economy-wide prohibition on unfair trading practices, such as manipulative user interface designs (“dark patterns”) and hidden fees, to better protect consumers.27

U.S. National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA)

In its February 2023 report on the mobile app ecosystem, the U.S. NTIA reached similar conclusions. The report stated that the policies of Apple and Google have “created unnecessary barriers and costs for app developers,” leading to a state of competition that is “suboptimal”.55 The NTIA recommended that policymakers consider measures to limit restrictions on sideloading, competing app stores, and alternative in-app payment options to foster a more competitive environment.55

Consumer Reports

Independent consumer advocacy groups have also weighed in strongly. Consumer Reports, for instance, applauded the U.S. Department of Justice’s antitrust lawsuit against Apple. The organization stated that Apple has “harmed innovation and competition” by limiting access to its hardware and software for competing services like smartwatches and contactless payments, ultimately limiting consumer choice.56

Synthesis and Forward Outlook: The Future of the App Economy

The evidence from judicial rulings, new legislation, and stakeholder advocacy across key global markets leads to an unequivocal conclusion: the era of the unchallenged, tightly controlled walled garden is over. A combination of legal pressure and regulatory intervention is irrevocably prying open the mobile ecosystems of Apple and Google. This transition, however, is not leading to a single, uniform model but rather to a new, more complex and contested global landscape defined by a patchwork of judicial remedies and legislative mandates. As this new reality solidifies, it raises a series of critical, unresolved questions that will define the future of the app economy.

Key Unresolved Questions

Global vs. Regional Implementation

A central strategic question for platforms, particularly Apple, is whether they will be forced by market pressure and regulatory complexity to adopt their most open policies globally, or if they will attempt to maintain a fragmented system of region-specific rules. Complying with distinct, detailed regulations in the EU, Japan, Australia, and potentially other jurisdictions in the future, while maintaining a closed system elsewhere, presents significant technical and administrative challenges. The path of least resistance may eventually be to create a single, global developer policy that complies with the strictest combination of these regulations.

The Future of Commissions

The foundational business model of the app stores—the 30% commission—is under existential threat. The question is what will replace it. It is unlikely that commissions will drop to zero, as platforms still provide valuable services. A more probable outcome is the “unbundling” of the commission into a more complex system of fees for discrete services. This could include a base fee for app distribution and discovery, a separate processing fee for using the platform’s payment API, an additional fee for security services like app notarization, and perhaps premium fees for promotional featuring. This would create a more transparent, albeit more complicated, pricing structure for developers.

The Real-World Impact on Security and Innovation

The most significant unknown is the tangible impact these changes will have on the ecosystem. Once alternative stores and payment systems are widely available, what will be the measurable effect on malware rates, user privacy, and the pace of app innovation? The platforms’ dire warnings of a security crisis will be put to the test. It remains to be seen whether a competitive market for app stores will lead to greater consumer choice and lower prices, as proponents argue, or if it will result in user confusion, a race to the bottom on security standards, and the proliferation of fraudulent or malicious apps.

Strategic Outlook

For Developers

The new landscape presents a duality of opportunity and challenge. The opportunities are clear: the potential for lower commission fees, the ability to establish direct customer relationships and billing, and freedom from the often-opaque and arbitrary enforcement of app store review guidelines. The challenges, however, are substantial. Developers will face the complexity of navigating different rules across various jurisdictions, and those who opt out of the platforms’ integrated systems will take on the increased responsibility and liability for payment processing, fraud prevention, and customer support.

For Platforms

For Apple and Google, the strategic imperative is to adapt their business models from gatekeeping to value-added competition. Their ability to generate revenue will increasingly depend not on their control of distribution channels, but on their ability to convince developers to voluntarily use their services. This will necessitate a shift in focus toward providing best-in-class tools, APIs, security services, and a superior user experience that developers and consumers are willing to pay for, even when alternatives exist.

For Policymakers

The work of regulators is far from complete. As demonstrated by the compliance battles in the United States, passing a law or securing a court order is only the first step. Continuous monitoring and robust enforcement will be required to prevent “malicious compliance” and to ensure that the spirit of these new regulations is upheld. Furthermore, as technology evolves, particularly with the rise of new paradigms like generative artificial intelligence—an area of emerging concern for the ACCC—regulations will need to be adapted.27 The need for enhanced international regulatory cooperation through forums like Australia’s Digital Platform Regulators Forum (DP-REG) will become even more critical to ensure a cohesive and effective global approach to governing the digital economy.58